|

14.4 Selling

Bird Photos

The idea of making a living by

taking and selling bird photos—i.e., spending most of your day

photographing birds and then spending a small fraction of your time

selling the photos for a considerable profit—is a wonderfully quaint

illusion that is both very attractive and potentially very difficult to

fully dispel. The problem isn’t that bird photos can’t be sold for profit, but that

doing so consistently over the long term in a financially sustainable

way seems to be the privilege of a lucky few. Certainly, the

prospect of trying to pay a mortgage and feed a growing family by

selling the occasional “lucky shot” is more than a bit terrifying.

Nevertheless, it is certainly possible to sell your

bird photos, as long as you’ve got something that somebody somewhere in

the world would really like to own. Depending on how much time

(and money) you’re willing to spend, larger or smaller numbers of sales

of your works may be correspondingly feasible. Whether this

translates into an actual profit,

after subtracting all of your costs (whether including equipment costs

or not), is another question.

For digital photos, one option with much promise is

to sell them via the internet. There are now many web sites (ImageKind, SmugMug, ArtistRising, to name just a few)

that will both host your photos and fulfill print orders from internet

customers. These businesses use a print on demand model: they don’t

actually make the physical print until they receive an order from a

customer. When the order comes in, they print the image at the

requested size, frame it, and ship it directly to the customer.

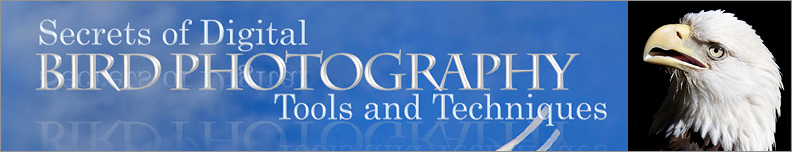

Fig. 14.4.1 : Selling photos via ImageKind is a snap. Once you’ve

uploaded high-

resolution image files, customers will be able to order prints in any

appropriate

size, with or without a frame and/or mat. They can also print

canvases. Other

companies provide similar services, though most charge the photographer

an

ongoing maintenance fee. As of this writing, ImageKind still

offers a free account

with very, very few practical limitations, and their product quality is

very good.

They handle the financial transaction (i.e., charging the customer’s

credit card) and send you a check when your earnings have exceeded some

minimum amount. I’ve never had any luck with this model, but

others have, and it’s certainly worth looking into. Note that

some outfits charge a yearly or monthly fee, so that in order to be

profitable you’d have to make at least enough to cover that cost.

More information on internet hosting sites is given in section 16.1.

A rather different approach to internet-based sales

is the so-called stock photography

option. When commercial organizations (e.g., magazines,

advertisers, book publishers) need a photo of a particular type (such

as an ocean sunset with some seagulls flying by), they typically

fulfill that need by visiting a stock photo agency and performing a

search through their archives for a suitable image. If one is

found, the requester pays a licensing fee for the use of the

image. A portion of that fee is then paid to the

photographer. Such royalty payments for individual photos can

range from a few dollars to a few hundred dollars, but are typically

very small. However, successful stock photographers with enormous

portfolios on file with a stock agency can rack up sizeable quarterly

payments if their images are used frequently enough.

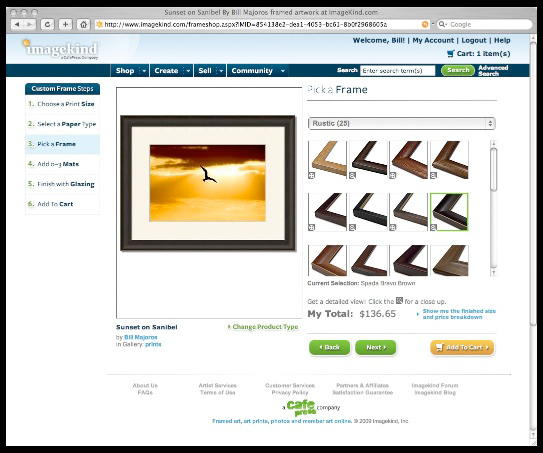

Fig. 14.4.2 :

Selling your photos to stock agencies can potentially

generate significant revenue. Some of the drawbacks are that

the submission process can be frustrating, the types of photos you

take may not be in demand by an agency or its clients, and any photos

that are purchased aren’t likely to end up on anyone’s wall or to show

up in National Geographic magazine.

Submitting images to a stock agency isn’t

trivial. They tend to have very strict image quality

requirements, and the agents responsible for accepting or rejecting

submissions can be highly fickle. Also, certain types of photos,

such as those of bald eagles, are in such great supply that all of the

ongoing demand can be handled from images already aquired long ago;

thus, even the world’s most beautiful shot of a bald eagle can be

rejected by an agency simply due to their already having more eagle

shots than they need. Note that stock photography is very

different from fine-art photography:

stock photos are mostly used for illustration or for backgrounds in

advertisements (such as for beach resorts, tropical cruise lines,

realtors, etc.), not for producing wall art. A stock photo

needn’t be aesthetically pleasing all, as long as it has value as an

illustration. For photographers obsessed with capturing the

beauty of nature in aesthetically pleasing images, the idea of stock

photography can be a bit of a turn-off.

In terms of

physical (i.e., non-internet based) sales of photos, there are a number

of potential venues. Though they all have certain “barriers to entry”, some are easier to overcome than

others. One of the easier venues to get into is the art fair. Though some art

festivals are juried, meaning

that a panel of judges assesses your work before deciding whether to

allow you to participate, many are not. For the latter events,

the only barrier to entry is typically a registration fee, which I’ve

seen range from $40 to $65 (US); fees for prestigious, big-city shows

(in New York City, for example) can be higher. Obviously, for the

event to be financially worthwhile, you’d have to make enough sales to

recoup the entry fee and any other costs incurred in preparation for

the show.

Fig. 14.4.3 :

My photos on display at an art fair. Every fair is

different. This one was

spread out over several city blocks, with the art being displayed in

stores, theaters,

cafes, and dedicated galleries. Setting up your display takes a

lot of work, and then

standing there for eight hours while greeting hundreds of viewers takes

even more energy.

Even if you don’t make much money from sales, listening to people

praise your work is

gratifying in itself, and noting which photos seem most popular can be

useful later.

Note that sales precipitating from art shows can

sometimes happen days or even weeks after the show, when visitors to

your booth (who took your business card) contact you to arrange for the

purchase of a particular piece. Sometimes prospective buyers just

need more time to think about a big purchase (a $300 or $500 canvas,

for example). These are the people you most want to ensure have

your business card before they leave your booth. If you don’t yet

have a business card, it’s the first thing you should look into.

Colorful, glossy business cards with your name, email address, and the

web URL of your online gallery are extremely cheap nowadays; I get mine

from OvernightPrints.com, but

there are many other companies that can print them quickly and

inexpensively for you. Having at least several hundred of them on

hand at an art show is a good idea.

Fig. 14.4.4 :

An attractive business card may be a

greater asset than you realize. Anything that can

spark a discussion with the potential customer is

a valuable tool. Remember that buying art isn’t

like buying underwear. Customers want to know

something about you and your process; any infor-

mation you give them can increase the perceived

value of the works you’re trying to sell.

Leaving the back of the card blank

is a good idea, so that you or the customer can write notes on the back

(such as a price quote). I also recommend using your best

bird image as the background for the card (on the front of the card,

but behind the text), so that people can instantly remember where they

got the card, later when they come across it at home. Having a

striking image on the card itself can also trigger more conversation

when the customer takes note of it while standing in your booth,

keeping the customer there longer and giving him/her more time to

ponder your work. For many art collectors, the desire to own an

artist’s work is partly a function of their interest in the artist, in addition to the

aesthetic value of the work itself. Engaging the customer in

conversation about your work can help to plant you and your work into

the customer’s memory, possibly leading to sales at a later date.

Fig. 14.4.5 :

In addition to your large, framed prints or canvas wraps, it’s a good

idea to have some smaller items for sale at more modest prices.

While the number

of people willing to cough up $300 for your larger works may be

limited, the number

willing to part with $15 for an 8×10 may be much,

much higher.

In addition to large, framed prints or canvases,

it’s a good idea to have some smaller, cheaper items for sale.

There are a number of possibilities here. The simplest is to just

have some small prints on hand, preferably wrapped in a clear,

protective packaging such as those sold under the name ClearBags; you can also just buy a

large roll of clear plastic wrapping from your local art store (e.g., Michael’s) and then wrap this

around each piece and close it off with scotch tape. Since

unframed / unmatted prints are flimsy and prone to being bent or torn,

it’s best to provide some firm backing. Many people use matboard for this purpose, but I

prefer to have my prints mounted onto masonite

or styrene, because it gives

the piece more heft and makes the customer feel that they’re getting

more for their money.

Fig. 14.4.6 :

Masonite prints are both economical and practical. They’re

more durable than loose, paper prints. They feel more “solid” than

matted prints. They can easily be framed, or simply propped up on

a

table or desk as-is. When selling them, you should package them in

a clear, protective enclosure to protect the front surface from

scratches.

Another option is gatorboard,

which is an especially strong type of matboard. Some pro photo

labs can affix your photo permanently to one of these types of

substrate, for a nominal fee. Once it’s placed in a clear plastic

package, it’s relatively safe for transport by customers. I also

like to put a sticky label on the back of each of my prints, with my

name and web site address printed on it, in case the buyer later wants

to contact me about buying some more pieces. An especially nice

option is to use the extremely inexpensive gold-leaf “address” labels that you can order from

any number of online outfits. I use a company called 123print.com, which allows me to

customize the label online when placing my order.

Fig. 14.4.7 :

Gold-leaf “address” labels are an

attractive and inexpensive way to

“sign” the back of

your works and remind buyers where they can go to get more

photos from the same artist.

As mentioned previously, art fairs can require an

enormous amount of work, and can result in a disappointing number of

sales. At a recent show I netted about $95 (US), which after

subtracting the $65 registration fee left me with a $30 profit for 11

hours of work (not including prep time before the fair)—far less than “minimum wage” here in the U.S. When I

factor in the cost of the easels and other miscellaneous items

purchased specifically for the show, I ended up having spent more than

I earned. I also ended up with lots of unsold pieces which I paid

to have manufactured. Gauging the number of prints to have

manufactured for an upcoming show can be very difficult. I’ve

found the forecasts of festival organizers (in terms of the expected

number of visitors) to be rather unreliable. Public turnout can

be affected by too many variables: the weather, proximity to holidays,

the scheduling of competing events on the same day, and even the price

of gasoline.

Even if the crowds do materialize at your booth,

there’s no guarantee that they’ll buy anything—even if they absolutely

love your work. During the last show in which I displayed my

work, the overall reaction of the visitors was so emphatically positive

that I began to feel embarrassed by all the lavish praise. And

yet, if I had a dime for every person who came by and effusively

praised my photos and then walked out without buying even a $10 print,

I’d be rich enough to run for public office. Keep in mind that

different art festivals see different demographics in their

attendees. Working-class people simply don’t have the disposable

income to spend on nonessentials such as “expensive” artwork—especially during a

recession. For this reason, it may be important to know

beforehand what type of clientelle can be expected at a show before

committing yourself to participate (i.e., before sending in the entry

fee).

Note that some art shows will even demand a certain

per-sale fee; I was recently approached by an organizer of an event in

which artists were obligated to pay 15% of their proceeds—in addition

to a $40 registration fee—to the organizing entity. On top of

these fees you’ll also need to take into account any sales tax that

needs to be paid. While some artists advertise their prices as “$xxx,

plus sales tax”, it can be simpler to just

incorporate the tax into the marked price. If you then round up

to the nearest whole dollar, you don’t need to worry about carrying

around a pocketful of heavy coins.

Fig. 14.4.8 :

Don’t forget about sales tax! In many states, artists selling

their art

at art fairs are required to collect and remit sales tax for all

transactions. In order

to do so you’ll generally need to obtain a “tax ID”, which in some

districts you can

register for online. (In the U.S., your “tax ID” is sometimes

just your social security

number). Contact your state’s department of revenue for specific

guidelines. In some

cases you’ll need to formally register a business in order to obtain a

tax ID.

If there aren’t many art fairs in your neck of the

woods, you might consider setting up a booth at a flea market and

trying to sell your bird photos there. This may be an especially

promising option just prior to the holidays, when people will be on the

lookout for unique gifts. Not all flea markets are dirty,

low-class affairs: in semi-affluent neighborhoods you can sometimes

find a weekly market—such as an extended farmers’ market that includes

local arts and crafts—with booths available at reasonable rates.

Seasonal craft shows are another option worth considering; I’ve often

seen a local photographer selling matted prints at the bi-annual craft

sale held at the local botanical garden. Just keep in mind that

outdoor craft shows bring their own challenges, especially in regards

to natural elements such as rain and wind. Such shows typically

require merchants to provide their own tents and tables, which has been

a limiting factor for me (since I drive a compact car).

One venue that I particularly like is the gift shop. At a local museum

where some of my large canvases were on display for several months, the

gift shop manager agreed to stock some of my prints, and this resulted

in a number of sales. Note that gift shops are typically highly

constrained in their available display space, so they must,

understandably, assess a commission on sales of artists’

works—sometimes as much as 40%. Every gift shop is different, but

it’s worth inquiring at any such shops in your local museums, zoos,

botanical gardens, and parks, to see if any will consider selling your

prints. Though you’re unlikely to accumulate any significant

profits through these venues, by affixing a label with your name and

web site address to each item, you can use these venues to increase

your exposure and generate more traffic to your web site; if you’re set

up to sell prints over the internet, the increased traffic to your web

site may result in greater profits than direct sales at gift shops and

art shows.

Fig. 14.4.9 : A

gift shop selling my prints (upper left) at a local museum.

Seeing your

photos for sale, for the first time, in a posh gift shop is a

thrill. Profits from sales in gift

shops can be rather meager, due to the hosting shop’s commission.

Remember that gift

shops are often small, and their display space can be very precious.

Though there

are commercial art galleries that also sell photography—even nature

photography on rare occasion—I’ve had no luck with these to date

(possibly through an extreme lack of persistent effort). What

entices me about these venues is that the clientele must obviously

expect higher price tags than the flea-market crowd, giving some hope

to the thought of actually making a solid profit from the occasional

sale. What leaves me rather more hesitant is the character of the

so-called “art” I’ve seen on display in some of

these places. More generally, I’ve found city art circles to be

rather light on the inclusion of nature-themed works, so I suspect that

art shows and galleries located in cities may be a difficult sell for

the aspiring bird photographer.

Wherever you do finally decide to try selling your

avian art, there remains the issue of deciding how to price your

works. I like to think in terms of two separate product lines:

the relatively inexpensive prints priced under $50 (US), and the more

costly framed pieces or canvases starting at $100 and ranging up to

$500 or more. For the simple prints (whether loose or mounted on

masonite or matboard), since they’re intended mostly to generate

exposure and the potential for future sales of more expensive pieces, I

recommend pricing them in line with whatever other artists in your

venue are charging for similarly-sized items. I generally add a

markup of between 10% and 100% on these, depending on the venue and the

expected clientelle.

For the more expensive items, such as large, framed

prints or canvases (i.e., gallery wraps), a good rule of thumb is to

price each piece at roughly three times the manufacturing cost, and

then to adjust upward or downward depending on other factors, such as

the popularity of the piece. Based on the limited data I’ve

been able to collect so far, lowering the prices on these higher-end

items doesn’t seem to result in more sales, and indeed, the

conventional wisdom in art circles is that offering extremely low

prices is a bad idea. At a recent art fair I started out applying

a 200% markup (as per the above rule-of-thumb) and then gradually

reduced the markup over the course of the fair until I had reached 0%,

and found that the price made absolutely no difference in sales—people

lavished my photos in (undeniably genuine) praise, but refused to buy

the larger pieces at any markup level, including 0%.

|

|

|