|

6.7 Selecting AF Points

As we described in section 2.6,

the standard autofocus mechanism used by DSLRs (except when in live

view mode) is based on one or more tiny strips of pixels called autofocus sensors, or AF points. In many cameras,

you can see

a representation of the AF points by looking into your viewfinder:

they’ll appear as tiny squares or diamonds, usually arranged into a

regular pattern that spans much of the visual field. In some

cameras they’re only visible when the autofocus is actually engaged,

and may change from black to red when the camera believes it has

achieved perfect focus. Note that these squares or diamonds that

you see in the viewfinder only represent the general locations of the

individual AF sensors; in general, the actual AF sensor may be larger

or smaller than the glyph seen through the viewfinder.

There are a number of factors that need to be

considered when deciding which AF point(s) to use in a given

situation. Obviously, you’ll always want to make sure that the

selected AF point(s) are positioned on the bird in the viewfinder,

rather than on other features of the scene such as branches or leaves,

or even other birds besides the one you’re concentrating on capturing

most prominently in the image.

Perhaps the simplest strategy to begin with is to

use only the center AF point, and to always keep the bird positioned in

the center of the frame. When autofocus is engaged (by pressing

the shutter-release button halfway), the camera will focus on the bird,

since the center AF point should be positioned on it. If you’re

close enough (or using a lens with enough magnification), the bird may

be large enough in frame that you can position the center AF point on

just the bird’s face, or just on its eye. This is typically what

you want, since bird photos almost always look best when the bird’s eye

is perfectly in focus, even if some other parts of the bird are out of

focus.

Fig. 6.7.1 :

Anhinga in shallow focus. In most cases the bird’s eye is what is

most

important to get in focus. At shallow DOF’s, ensuring that the

eye is perfectly focused

can be difficult. In this case I used center-point AF on the

forehead and then slightly

recomposed to put the head higher in the frame. (1/125 sec,

f/7.1, ISO 125, 600mm,

manual mode, TTL flash)

If the bird is very large in the frame, then you may

find that positioning the center AF point on the bird’s eye results in

some important part of the bird’s body being clipped (i.e., not visible

in the viewfinder—keeping in mind that your viewfinder might only

show you 95% or so of the actual frame seen by the camera’s imaging

sensor). There are two solutions to this problem (other than

using less magnification). The first is to simply use another AF

point. If your camera has lots of AF points, you can simply tell

the camera to use the one closest to the bird’s eye (precisely how to

select AF points differs from camera to camera, but usually involves

pressing a button and then turning a dial until the AF point that you

want is highlighted in red). If the bird is stationary and you’re

not worried about getting rapid follow-up shots as the bird takes to

flight, then selecting a non-center AF point closest to the bird’s eye

is generally ideal. If you think the bird may soon take to

flight, and you're hoping to track it during its flight (using servo AF

mode), then there may be some risk involved in using a single,

non-central AF point, since that point might not be ideally positioned

for AF tracking of the bird in flight.

Fig. 6.7.2 :

Using a non-central AF point. Because the bird was facing to the

left,

I decided to position my subject on the right, requiring a non-central

AF point.

Alternatively, I could either have used the center AF point and

recomposed, or

used the center AF point and then cropped the image to the desired

composition.

(1/640, f/5.6, ISO 400, 560mm, Av mode, TTL flash)

The other option for focusing on a part of the bird

that is not positioned in the center of the viewfinder is to use the focus-and-recompose method.

In this method, you first position

the central AF point on the bird’s eye, press the shutter release

halfway until the camera achieves focus (usually indicating the fact

via an audible beep, or by flashing the AF point in the viewfinder),

and then recompose—that is,

adjust the camera’s angle so the bird

is now positioned however you want it within the frame. As long

as you keep the

shutter release pressed halfway (and assuming you’re in one-shot AF

mode), the bird’s eye should stay more-or-less in focus even though the

enabled AF

point is no longer positioned on the eye. When you're ready you

can press the

shutter-release the rest of the way and take the shot.

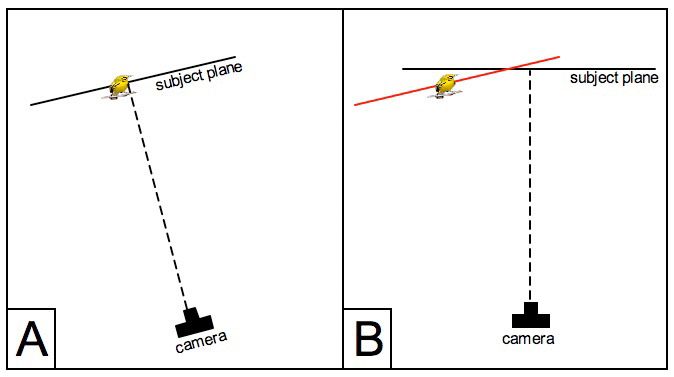

The focus-and-recompose method is very popular, and

can be extremely effective. It’s important to be aware of a

potential problem with this method, however. The problem is best

understood by first viewing the situation geometrically, as in Figure

6.7.3, below:

Fig. 6.7.3 :

One of the dangers of focus-and-recompose. Left: the camera is

(auto) focused on

the bird, defining a focus plane that contains the subject.

Right: after recomposing (rotating

the camera through a small angle), the focus plane no longer contains

the subject, so the

bird may be slightly out-of-focus. If the DOF is large enough,

relative to the angle of rotation,

the bird will still look sharp. Zooming in on the playback image

after taking a recomposed

shot can help you detect focus problems, as long as your camera’s

playback images are

of high enough resolution (some cameras show only low-res preview

images).

In the spirit of theoretical physics and its much-celebrated “perfectly

spherical cow”, let us assume a perfectly flat

bird, occupying a single

plane, as depicted in part A of the figure above. As shown in

part B, after recomposing, the plane occupied by the bird no longer

coincides with (though it does intersect) the plane the camera is

focused on. As a result, the bird may appear slightly out of

focus in the resulting image. Exactly how much out of focus

depends on the depth-of-field (DOF). Recall from section 3.13

that

DOF can vary, based on aperture and distance (as well as pixel

size—but we’ll ignore this fact, since for most DLSRs the pixel size

is effectively fixed). Thus, in the figure above we should in

practice replace the thin lines (representing planes) with thick, fuzzy

lines (representing plane-like volumes). If the thickness of the

resulting plane-like volumes is great enough, and the angle involved is

small enough, the act of recomposing may not result in any discernible

loss of sharpness in the final image. And this is indeed what is

often seen in many cases, which is why focus-and-recompose

continues to be a popular method. Just be aware that

focus-and-recompose has at least the potential

to result in

out-of-focus images, especially at wide apertures and short distances,

and check for this regularly when shooting in the field. Whenever

I use this method, I always zoom in on the bird’s eye on my camera’s

LCD screen (after taking the shot), to make sure the eye looks sharp.

One other issue to be aware of when using

focus-and-recompose, if you’re not using manual exposure, is that the

method can sometimes result in exposure problems. On some cameras

(and for some metering modes), the camera’s metering function is linked

to the selected AF point. If after acquiring focus you then

recompose, with the AF point now positioned elsewhere in the scene

(i.e., no longer on the bird), the

measured light level read by the camera’s meter may represent the

luminance of the background more than that of the bird. As a

result, the bird itself may

end up being over- or under-exposed. There are a number of

solutions to this problem. One is to simply use manual exposure

and find the proper exposure for the bird; then you can recompose all

you want and shouldn’t have to worry about confusing the camera’s

meter, since you’re not using it. If you prefer to use spot

metering, then the best solution would be to use your camera’s auto-exposure lock, or AEL,

feature. When metering is linked to

the selected AF point, you can use AEL to force the camera to take its

meter reading at the same time that it performs autofocus (or when you

press the AEL button)—i.e., when

the AF point is positioned on the bird, before recomposing. On

some cameras this can be a bit tricky, because you may have to press

and

hold an additional button (AEL) while still holding down the shutter

release halfway, all the while concentrating on the most aesthetically

pleasing angle for recomposition. Another option is to use a

different metering mode, such as evaluative metering, which should be

less affected by recomposition (on average).

Instead of using just one AF point, on most DSLRs

it’s possible to enable all points, or just a subset of all available

points. The subsets that can be selected are often arranged in

ring patterns, so that you can, for example, select just the centermost

cluster of points, or just a ring of points around this central

cluster, or perhaps a ring of points more toward the periphery of the

frame. When multiple AF points are selected, the camera assesses

the initial focus of the scene through all the selected AF sensors, and

then makes focusing decisions based on the information from those

selected sensors. Precisely what strategy is used for achieving

focus based on the set of active AF sensors differs between

cameras. Depending on the camera model, the AF system may try to

achieve perfect or near-perfect focus for the largest possible subset

of

selected AF sensors, or it may try to ascertain which AF point

is positioned over the closest part of the scene and then perform

focusing based on just that AF sensor. Regardless which strategy

your particular camera uses, it’s important to note which AF sensors

(among those that you’ve enabled) the camera has chosen to actually

use—these will typically be indicated via red flashing inside the

viewfinder. If, for example, you enable all AF points, you may

find that the camera chooses a subset of points corresponding to the

branch that the bird is perched on, rather than the bird itself.

In that case you’d obviously want to try enabling a different subset of

AF points, if possible, or to switch to single-point focusing. I

typically don’t use more than one AF point unless I’m trying to track

birds in flight, and even then I often use just one AF point.

Fig. 6.7.4 :

Eagle head-on. When the subject is oriented head-on, the profile

visible

to the autofocus sensors can be relatively small. By using an

array of AF points

rather than just one, your camera may be better able to keep the bird

in focus

during the approach. Note that the background of this image was

processed

in Photoshop to make it more interesting; replacing the background of

an image

is discussed in Chapter 13. (1/6400 sec, f/8, ISO 800, 840mm, Av

mode with

-2/3 EC, no flash)

Note that on many high-end cameras there are “invisible” or “helper” AF sensors that you may not see

in the

viewfinder, or may not be able to explicitly select or enable/disable,

but that can influence the focusing strategy of the camera. These

can typically be globally

enabled or disabled via a “custom fuction”

setting deep within the camera’s menu system. As noted in section

2.6, features such as “AF point expansion” that intelligently modify

your selected set of AF points can sometimes help to keep a flying bird

in focus, especially if you’re having trouble keeping the AF sensor(s)

positioned on the bird in the viewfinder during its flight.

However, these features can sometimes be more of a hindrance than a

help, since they may, for example, result in the camera moving the

selected AF point from the bird you’re following to another bird in the

frame. These issues are very camera-specific, and will generally

require some research and experimentation in order to become adequately

familiar with how your camera behaves under different custom function

(CFn) settings. Some

camera companies publish “white papers”

giving advice for how to optimally set the various CFn’s on a given

model, based on the shooting situation.

On most cameras there are situations in

which you’ll be limited to using only the center AF point, such as when

using teleconverters or a lens with a maximum aperture of f/5.6 or f/8. I don’t

find this to be a severe limitation, since I

typically use only the center AF point, except when tracking

erratically-flying birds, in which case I may switch to enabling an

appropriate group of points (such as a ring-shaped array), with or

without automatic point expansion.

Fig. 6.7.5 :

Red-shouldered hawk chicks in the nest. Because a 2× TC was used in

combination

with an f/4 lens, the maximum aperture of f/8 limited me to using the

center AF point. This image

is heavily cropped from the RAW file. Since the distance was

great, DOF was large and focus-and-

recompose worked fine. (1/400 sec, f/10, ISO 200, 1200mm, manual

mode, TTL flash at +3 FEC)

Note that for birds that don’t fill the entire

frame, an alternative to focus-and-recompose is to simply keep the bird

positioned in the center of the frame during shooting, and then to

later crop the image on the computer. While cropping you can

choose a crop window that places the bird in the most pleasing position

in the resulting frame. Even though I only have a 10 megapixel

camera, I crop most of my photos to 50% or less of the original size,

and typically do my recomposing (i.e., positioning the bird outside the

center of the resulting frame) then rather than while actually shooting.

|

|

|