|

16.2 Building a

Custom Web Site

While the mass-market, “pre-canned” photo-hosting solutions are a

great way for beginners to

start sharing their bird photos on the internet, at some point you may

decide that you’d really like to have more control over the

presentation of your digital portfolio. For example, you

might be very picky about the layout of your digital “gallery”, in

terms of the geometry or background colors of the web page,

the way different images in a gallery (or even different galleries) are

displayed relative to each other, or even just the resolution and

scaling of the full-sized views of individual photos.

Artistically, it’s quite natural to want to control every aspect of the

viewing experience enjoyed by your gallery’s visitors, and to the

extent that you feel you have a unique and artistically satisfying “vision” for a given collection of images,

it’s worthwhile putting in

the effort to realize that vision for the viewer’s benefit.

Although some photo-hosting sites do allow for some

degree of customization of individual photographers’ web pages, you’ll

typically have to upgrade to a “premium” (i.e., non-free) account in

order to take advantage of those options. In some cases, the

range of options for predefined “page styles” may meet with your

satisfaction, and if the associated hosting fee and other

considerations (whether practical or artistic) are satisfactory, then

you may indeed consider yourself lucky and decide on that particular

solution. Just keep in mind that not all media-hosting sites stay

in business indefinitely, and even those that do survive over the long

term may impose changes in account-holder agreements and/or limitations

that you might eventually find unacceptable.

Fig. 16.2.1 :

My personal bird-photography web site. At the top is the banner

and the web site title; below this is the main menu (largely invisible

here). I’m

constantly thinking of ways to improve the visual appeal of my online

gallery.

With a do-it-yourself web site, you can change the appearance in any

way you want.

The other option is to build your own web site from

scratch, and while that may sound like a lot of work (which it is),

most serious photographers seem to end up adopting this solution

eventually.

Note that while this solution is not trivial to implement, it needn’t

be expensive, and indeed it can be cheaper than using a

pre-canned solution, in some cases. In this section we’ll

consider

the main issues involved in the do-it-yourself route to

online photo hosting.

16.2.1

Choosing a Hosting

Company

The first thing you need to do is to pick a domain name. This is the web

address (“URL”) for your main web site.

Two popular options are to use

something like “yourname.com” (i.e., “JaneDoe.com”, but with your name

substituted in place of Jane Doe), or to coin a catchy site name and to

use that. For example, my personal web site (which I use for bird

photography as well as other uses) is BillMajoros.com, while for my

bird photography I chose the name ThirdBirdFromTheSun.com, since the

phrase “Third Bird from the Sun” is catchy and therefore easy for

people to remember. Try to brainstorm a list of possible

domain names, including both of the above types (i.e., those based on

your name, and those based on a catchy bird-oriented or

photography-oriented phrase). You’ll then want to check which of

these domain names are available

(i.e., which haven’t already been taken by other people). You can

do this easily at any number of domain-registration

sites; one reputable registrar is NetworkSolutions.com.

Note that you can use any of these domain “registration” sites to check

for domain availability; just querying domain availability doesn’t cost

anything, and you don’t have to register the site you

want through the company that did the search for you (that is, you do need to register the site you

want with some registrar, but

it needn’t be the same

company who did the search for you to determine availability).

Domain name registration typically costs in the $10 (US) range, give or

take a few dollars, and it needs to be renewed every year (generally at

a comparable price).

In addition to selecting a domain name, you need to

select a web hosting company.

This is the company that provides the actual storage space for your

site, as well as the hardware and software that “serves” the site to

browsers over the internet. Hosting plans typically run $5 to $10

(US) per month, which is extremely reasonable considering that such

plans typically provide far more space and bandwidth (monthly upload/download

quota) than you’re ever likely to need for a bird photo website.

For example, as of this writing my current provider (IPOWER.com) offers

unlimited disk space and unlimited bandwidth for

$5.95/month for a 1-year commitment, or $6.95 for a monthy

commitment. These prices often change, however, so be sure

to check the hosting company’s web site for current pricing.

Fig. 16.2.2 :

My current hosting company’s main web page.

Don’t be fooled by the hype.

Once you’ve found an available domain name and a

hosting package that you like, you can register the domain through your

chosen registrar when purchasing their hosting plan.

They’ll typically charge you separately for the domain registration and

the hosting plan; some hosting plans include one free domain

registraiton, though yearly renewals of the domain name will

incur an additional cost. Note that registering your domain name

through your hosting company is generally the best option; though you

can certainly register the domain name through a different company,

getting your hosting company to do the registration generally

simplifies things, since the hosting company can internally coordinate

the registration and IP/DNS pointing of the domain (don’t worry if you don’t know what that means).

Apart from quota

limits (i.e., how many gigabytes-worth of files you can store,

and how many gigabytes can be transferred to viewers, per month), there

are some other differences between hosting companies that you should be

aware of. The first is ease of

use (for you, not your visitors). Unless you happen to be

a computer scientist like me—and possibly even if you are—it’s

likely that you’ll want for your hosting company to provide an

intuitive interface for common maintenance issues such as backups, domain/subdomain pointing, and access statistics. The

hosting company that I use provides a web-based “control panel” that

provides some of these functions (see the figure below).

Fig. 16.2.3 :

The control panel for my web hosting account. The only feature

I use with any regularity is the Visitor Statistics report.

Although

graphical user interfaces like the one shown above can be useful for

some tasks, the actual designing of web pages and uploading of photos

to the host server is typically easier when done using other tools, as

we’ll

describe shortly. I generally only use my host’s web-based

interface when checking available disk space and bandwidth, collecting

visitor statistics, or managing subdomains. Regarding disk space,

most hosting plans these days provide a ridiculously large amount of

disk space, so it’s generally not an issue even if you plan to upload

many, many thousands of photos; I have thousands of bird photos on my

web site and they only take up about 6 gigabytes (GB) total. So

far I also haven’t had any issues with bandwidth—the amount of data that

can be uploaded or downloaded per month—since photos resized for

viewing on a web page are typically very small (~200 kilobytes on

average, where 1000 kilobytes = 1 megabyte, and 1000 megabytes = 1

gigabyte) and bandwidth limits are

typically very large (say, 250 GB per month).

Most hosting companies will also provide a way for

you

to see your site’s monthly access satistics—i.e., how many people

came to your site this month, how many web pages they viewed, how many

images, and even which pages and images were accessed most. This

can be very useful if you’re thinking about trying to sell some of your

photos, or to enter them into photo contests. Just keep in mind

that download statistics can be misleading: an image may be viewed more

frequently than others simply because someone posted a link to it

somewhere on the internet, and many other people followed that link;

that doesn’t necessarily mean that that particular photo is the one

people like most in your portfolio.

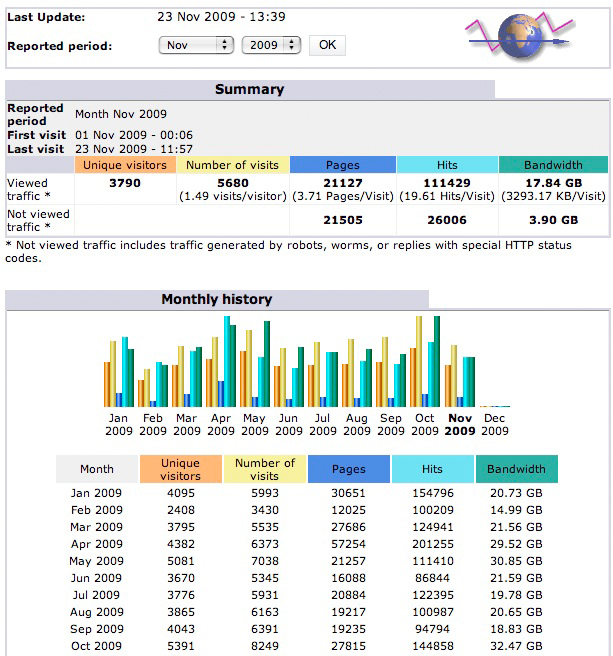

Fig. 16.2.4 : A

small portion of the Visitor Statistics report for my web site.

The rest of the report (not shown) goes into great detail about the

types of

files most frequently downloaded, the names of those most popular files,

the search engine phrases most often leading to a visit, and even the

operating system and browser version statistics of visitors.

Stats can

be viewed on a per-month basis, but are continuously updated.

One very

important consideration when choosing a hosting company is the

reliability of that company’s service. If the company’s servers

often crash, then you may find that your web site is often inaccessible

to people who want to view it. When the servers crash, it may be

hours or even days before your web site is visible again. Even if

the servers don’t crash very often, they may be overloaded by too much

traffic, resulting in web pages that load very slowly. Internet

users these days have little patience for slow web servers, so if you

get stuck on a slow server, you may find that people spend very little

time at your site. I’ve had a number of cases in which I couldn’t

upload a large number of photos because the servers kept dropping the

connection after the first few photos were sent, and I was told by

customer support that the server was simply overburdened by other users

who shared the server I was on.

A related issue is the competence of the hosting

company’s technical support staff. Although the hosting company

that I use claims to have exceptionally competent staff (“experts in

the industry” is what their web site

proclaims), I can say with

absolute certainty that many of them are substantially less competent

with a computer than my 13 year-old labrador retriever. Many of

the customer support staff are located overseas in call-support centers

where they don’t even have access to the servers or the engineers who

keep the systems running. I strongly recommend spending some time

browsing around in internet forums, reading comments from actual users

of various hosting companies, to find out which companies have the

highest server “up-time” and the most competent support

staff.

16.2.2

Creating HTML Pages

Web pages on the internet are encoded in a computer language called HTML. You

don’t really need to know this language in order to

create web pages, though it doesn’t hurt to know a little bit about

HTML if you’re thinking of building your own web site from

scratch. Later in this section we’ll cover some of the basics of

HTML.

Today, most web pages are created not by writing

HTML directly, but by using a visual web page editor that writes the

HTML for you. I like the Composer

program that comes with the Mozilla

package, which is completely free (see the Seamonkey product from mozilla.org). A

screenshot of Mozilla’s composer program is shown

below; this program is available for most common operating systems and

platforms (including Mac and Windows). Other programs for

composing web pages are available, such as Microsoft’s “Expression”

program; some versions of Microsoft Word also support web-page editing.

Fig. 16.2.5 :

The “Composer” program in the

Mozilla suite (now available as

part of the Seamonkey project). This editor is completely free,

and is what I’ve

been using for editing web pages for the past 8 years or so.

Everything is done

visually, via drag-and-drop. Tables (red dotted lines in this

figure) allow you to

organize content. Inserting images and links to other pages is a

snap.

In the example

shown above, I’ve created a web page visually, in Mozilla Composer, by

creating several nested tables

(indicated by the red dotted lines) and populating the cells of those tables with Images

And Words. As shown in the figure, you can easily set various

properties of tables and their cells, such as the spacing, alignment,

and color. None of this requires knowledge of HTML. For the

images, you can simply drag-and-drop them (in JPEG format) from a

folder on your computer

into the web page; you can then type in the accompanying text and

adjust the font size and color via visual controls in the Composer

program.

If you do happen to know a bit about HTML (or don’t

mind learning), Composer also allows you to edit the HTML directly, as

shown below. In this case I’ve designed a web page visually using

the user interface of Composer (i.e., without actually writing any HTML

by hand), and then clicked on the “HTML Source” tab, which causes

Composer to show the HTML that it has generated for the page; you can

then edit the HTML directly, if you like.

The HTML then needs to be saved into a file on your computer and

then uploaded to your hosting company’s server; note that any photos

displayed on the page have to be uploaded separately, since they’re not

actually embedded in the HTML file (the HTML source code simply “points” to the file by specifying its

location).

Fig. 16.2.6 :

Mozilla’s “Composer” program in

HTML source mode.

The source shown above was generated by Mozilla from the visual

layout that I designed using drag-and-drop operations (with the mouse).

A complete

tutorial on HTML programming is obviously beyond the scope of this

book; we’ll just briefly touch on some of its features. First, an

HTML file consists of both text

and markup; the former is

simply any text that you want to be displayed on the web page, while

the latter consists of special tags

that control the layout of the page and can also be used to display

photos. Each tag is delimited by greater-than and less-than

symbols, as in <h1> or <p>. Most tags come in pairs,

such as <b> and </b>, in which case the <b> tag

begins an HTML element and the </b> ends that element. Any

text sandwiched between a <b> and </b> will be displayed in

bold font, while

text between an <i> and an </i> will be displayed in italics. Top-level headings

can be specified using <h1>...</h1>, slightly smaller

headings by <h2>...</h2>, etc. Images can be

displayed using the tag <img src=“filename.jpg”>, which doesn’t

have an end tag (i.e., no </img>). To create a link to

another web page, you can use the <a href=“other_page.html”> tag,

which does require an </a> tag; the text between the <a...>

and </a> tags will comprise the link to the other page. If

you’re interested in learning HTML, there are any number of tutorials

available on the internet; a good place to start is the Wikipedia entry

on HTML, which lists several tutorial links at the bottom of the page.

If you happen to be a computer programmer, then

you’ve no doubt considered the possibility of writing your own custom

software for generating web pages to display your photo albums. I

use the programming language Perl

for this purpose; Perl is a popular scripting language available on

virtually all UNIX-based systems (including Mac OS X, which is built on

UNIX), as well as some others. I have one Perl script, for

example, which reads a directory containing bird photos and then

generates a web page containing links to those images. This

script is shown below (in part), in the UNIX editor emacs:

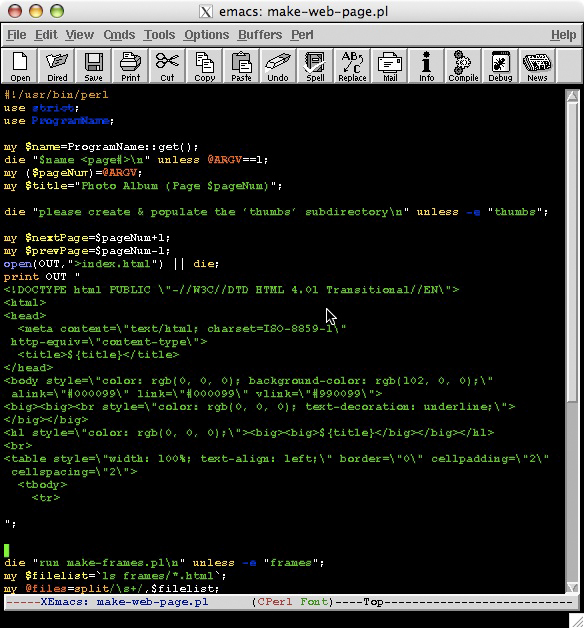

Fig. 16.2.7 : A

Perl script for generating an HTML-based photo album.

If you know how to write computer programs in any language, that can be

useful for building a pipeline for generating photo album web

pages. In my

system, all I need to do is populate a computer directory with image

files, and

then run several of my Perl scripts to create the thumbnails, generate

a set of

slideshow files, and assemble a gallery page. I also have Perl

scripts for

converting images from Mac to Windows, and for uploading to my server.

I have separate

Perl scripts for generating image thumbnails,

for making what I call frame files,

and for converting image gamma

settings between the native Windows and Mac settings. Thumbnails

are the small, icon-sized versions of photos that serve as

place-holders on the web page; when a user clicks on a thumbnail, the

larger version of the photo would then be displayed.

When displaying that larger version, I link to a special frame file rather than linking

directly to the image itself. The frame file is simply an empty

HTML file that contains nothing but the full-size image; I prefer to do

this because on some systems it will prevent the users’s browser from

resizing the image to fit inside the user’s browser window, which can

sometimes degrade image quality due to the browser’s crude image

resizing algorithm. The issue of gamma conversion will be discussed

in section 16.2.4.

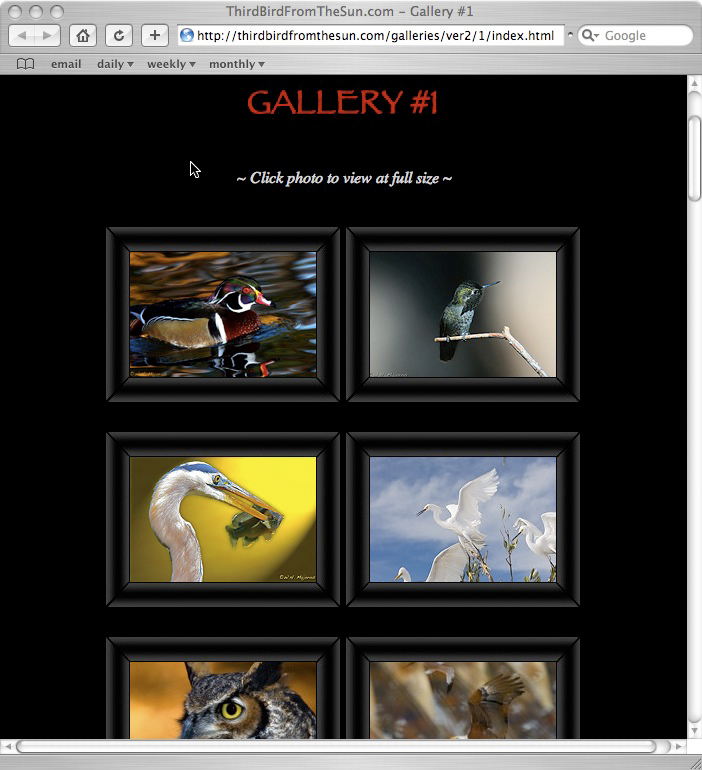

Fig. 16.2.8 :

Thumbnails in a photo gallery. When the user

clicks on a thumbnail, the browser displays a full-sized version

of the image. Choosing the thumbnail size, the background

color for the page (black here), and the spacing and overall

layout are some of the artistic decisions that have to be made

when designing a web site from scratch.

16.2.3

Site Organization

Once your portfolio reaches a certain size, you’ll want to begin

organizing it into a coherent structure that viewers will find

convenient to navigate. There are a number of different ways to

do this. For example, some birders organize their photos by

species, while others list their photo albums by date. I don’t

favor the by-species option,

since it tends to result in individual photo albums that have lots of

very similar-looking photos, resulting in some degree of

monotony. Instead, I organize my online photos into two main

groups: a “trophy case” of my hundred or so all-time best

photos, and a

separate index of photo albums organized by date (typically according

to individual photography trips).

Fig. 16.2.9 : A

portion of the top-level menu for my web site.

The topmost option takes the user to the list of photo galleries.

The bottommost option takes the user to the part of my site that

deals with sales of prints and canvases. The bird images along

either side are purely for decoration, to help make the menu

“come alive”.

In addition to

an index of photo albums, you might consider having a top-level menu

that offers links to pages containing contact information, a personal

biography, equipment info, and any merchandise (such as framed prints

or canvases) that you might have for sale. A biography can be

useful for giving your viewers a “mental hook” for them to associate

with your work (i.e., helping them to remember your work by remembering

something about you). Including equipment information can help to

increase traffic to your site from users with similar equipment who

perform an internet search based on camera or lens models. In

terms of merchandise, if you’ve set up a print-on-demand account with a

company such as ImageKind or SmugMug (see section 14.4),

then you can

simply link directly to that page from your main web site.

Another thing I recommend, to increase public

interest in your photo albums, is to invest the time to annotate your

photography with some meaningful text. If you group your photos

together according to some theme—such as location, or

species—you can then add some narrative describing how you obtained the

photos, or describing the species pictured, or the site where they were

photographed. Such text can be enormously useful in attracting

viewers to your site, because it will be indexable by search engines,

and will also provide an additional reason for some viewers to visit

your site. In fact, I believe the more text you add to your photo

albums, the greater your chances of attracting significant attention to

your photography. The text

can consist of anything from artistic essays or poetry to blogs and

diaries to reviews of equipment and/or birding sites. Literally

anything that might attract attention to your photo album is fair game,

when it comes to attracting the denizens of the internet to your

site. In a deeper vein, textual annotations increase the

intellectual value of your site by increasing the information content

and turning what would normally be just a random collection of JPG

files into a living, breathing, real person’s narrative about life in

the company of wild birds (or whatever you decide to write

about).

Note that once you’ve set up a hosting account for

your bird photos, you’ll typically have lots of space left over on your

account for hosting other web pages; these other pages can even have

their own domain names associated with them, since your hosting

provider can point those domain names at subdirectories of your hosting

account. For example, this book, which has as its domain name digitalbirdphotography.com, is

hosted on the same account as my personal web page, billmajoros.com. Also on this

same account is the domain for my biotechnology textbook (at geneprediction.org/book), the

domain for a DNA analysis software package of mine (genezilla.org), and of course my

bird photos (thirdbirdfromthesun.com,

which is currently aliased as birdpixels.com).

16.2.4

Platform Issues:

PC, Mac, and Gamma

It’s an unfortunate fact that images processed on one platform (such as

Windows) can appear quite different when viewed on another system (such

as on an earlier-generation Apple Macintosh). In

particular, images processed on an older Macintosh will

tend to look unnaturally dark when viewed in Windows, while images

processed on a Windows computer will tend to look “washed out” (i.e.,

too light) when viewed on the older Mac. The reason for this is

something called gamma, which

involves issues related to both hardware and software.

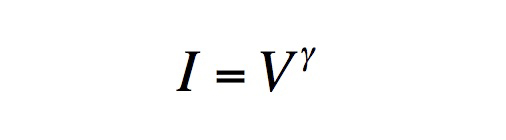

Mathematically, the gamma problem takes the form of

a power law relating image

intensity to applied voltage:

What this equation states is that the pixel intensity (I), as seen

on a computer monitor, is equal to the pixel value (V) encoded in the image file

(0 to 255, rescaled to the range 0 to 1), raised to the power gamma (γ). This nonlinear

relationship between encoded pixel value and rendered brightness is a

consequence of the underlying physics involved in the use of cathode ray tubes

(CRT’s—the predecessors of modern LCD screens) in rendering images;

to maintain backward compatibility, modern LCD screens (also called TFT displays) typically emulate the

gamma characteristics of traditional CRT displays. An example

gamma function is illustrated below. For Windows machines, the

value of gamma is typically 2.2 or 2.5, while for Mac systems (prior to

OS X 10.6, “Snow Leopard”), the value would be 1.8.

Fig.

16.2.10 : A gamma curve. The x-axis (horizontal scale)

Fig.

16.2.10 : A gamma curve. The x-axis (horizontal scale)

corresponds to the pixel values (1 to 255) given in the image

file, while the y-axis (vertical scale) measures the pixel intensity

produced by the physical display technology (e.g., CRT or LCD).

The exact shape of the curve is influenced by the gamma parameter,

which differs between different types of hardware.

The solution to this problem is to impose a gamma correction, by applying the inverse gamma transform

to the pixel values before sending those values

to the computer’s monitor (which will then apply its own gamma

transform). The combined effect of the inverse gamma transform

and the forward gamma transform is that the displayed pixel intensities

should (ideally) scale linearly with the encoded pixel values in the

original image file, as desired. The inverse gamma transform is

shown below:

You can apply this transform easily using the “convert

-gamma” command in the free, open-source

software package ImageMagick.

ImageMagick is available for all major operating systems, including

Windows and Mac OS X. Photoshop also has a gamma correction

function.

Unfortunately, not only can the

value of gamma vary between systems, but also some systems perform

their own gamma correction prior to sending the image to the monitor

for display; this complicates any strategy for cross-platform gamma

correction of bird photos. The strategy I’ve adopted is based on

an empirical approach. All of my bird photos are processed on a

Mac laptop. Because most web viewers use Windows, my bird photos

would appear unnaturally dark on their screens. So I process all

of my photos by applying the inverse gamma transform shown above (via

ImageMagick), with

gamma set to 1.38888. I determined this value of gamma by trying

different values and viewing the resulting gamma-corrected images on

several Windows computers (including both laptops and desktops with LCD

monitors); the value of 1.38888 was the one which resulted in Windows

images that most faithfully matched the originals when viewed on my

Mac. Note that this gamma value (1.38888) isn’t necessarily the

optimal value for correcting your own Mac-based images, since the ideal

value will be affected by the brightness of your native computer’s

screen.

Furthermore, Macs running the newest version of OS X

(version 10.6, also known as Snow

Leopard) now apply the same gamma transform as Windows machines,

so that an explicit gamma correction may not need to be applied to your

bird photos when posting them to Windows-dominated internet venues.

Systems other than Windows and Mac do exist, most

notably Linux (and other

flavors of UNIX), though at present they seem

to represent a very small percentage of the internet-browsing

population. Many Linux-based systems utilize the same gamma

transform as Windows, so if you’re processing images on a Linux

machine, you may not need to apply any explicit gamma correction before

posting your images on the internet. My personal solution to the

gamma issue is to ask users which system they’re using when they enter

my web site, and to then direct their web browser to a gamma-corrected

version of my site, as per their system. This requires

maintaining two parallel web sites (one calibrated to Windows machines

and one calibrated for Macs), but in practice this hasn’t been much

more than a minor inconvenience. (Note that if the figures in

this book appear unnaturally light or dark to you, then you may be

viewing the wrong version

for your operating system).

Fig. 16.2.11 :

The initial page of this book asks which system readers

are using, so that images scaled with the appropriate gamma value

can be used; using the wrong gamma for a given system will result

in images that are too bright or too dark.

Note that a gamma correction factor can sometimes be

specified system-wide in your operating system’s monitor profile, or in

your image processing software. Also, web browsers perform their

own gamma correction, which to some degree worsens the problem rather

than fixing it. Fortunately, the convergence of Mac and Windows

gamma values starting with OS X 10.6 should render the problem

increasingly irrelevant in the future.

A somewhat related issue is the use of special

browser plug-ins, such as the popular Flash

plug-in. Savvy web developers like to use flashy plug-ins because

they look sophisticated, but I try to avoid using anything other than

basic HTML, because plug-ins often aren’t available on mobile devices

such as cell phones and tablets.

16.2.5 Monitor Calibration Issues

Another unfortunate fact is that not every internet user is viewing

your web site on a properly calibrated display. You should,

however, ensure that your

monitor is properly calibrated, so that others viewing your photos on a

calibrated display will see more or less what you see when you view

your own web site. Also, postprocessing your photos on a

calibrated monitor will minimized the expected bias seen by the average

viewer using commodity equipment. The calibration key below can

be used as a quick check as to whether your monitor is out of

calibration. Section 14.1.2

discusses calibration techniques.

16.2.6

Making Web

Slideshows

Making a slideshow on the web is simple. The way I do it is to

have a separate HTML page for each image, and to link each HTML page to

the next. The code to do this is:

<html>

<body style="background-color: rgb(0, 0, 0)">

<center>

<a

href="next_page.html">

<img src="this_image.jpg">

</a>

</center>

</body>

</html>

The rgb(0,0,0) sets the page color to black, the <center> tag

causes the image to be centered horizontally on the screen, the <img

src...> specifies the image to be displayed on the current page, and

the <a href...> tells the system that clicking on the image

should cause the next page (with the next image) to be loaded into the

browser. Writing a computer program to automatically generate

these pages for a set of images in a directory is simple. It’s

a good idea to provide some instructions to the user on the very first

page,

so s/he knows how to get from one slide to the next, as illustrated

below.

Fig. 16.2.12 :

The top-level page for a slideshow on my web page.

It’s good to have a top-level instructional page to tell users how to

navigate through the slideshow. It’s also good to explicitly tell

users

that they need to click on the thumbnails to view images at full size.

I actually had a professor complain that the images on my site were

“too small”, until I

explained that those were only the thumbnails!

16.2.7

Avoiding Copyright

Infringement

It’s worth mentioning very briefly the issue of copyright. There are two

issues: making sure you don’t violate anyone else’s rights, and making

sure nobody violates yours. In terms of the former, the main

issue is the use of other people’s images on your web page. This

most commonly comes up in the use of icons. For example, in your

top-level menu you might want to use a Tweety Bird icon for the link to

your bird gallery, and perhaps a Scooby Doo icon for the link to photos

of your dog. These icons are easy to find by searching through

Google Images, but just because you can find them on the internet

doesn’t mean that using them isn’t a violation of the copyrights for

those images.

In terms of your own images, it’s a good idea to

place a copyright notice on your web site to protect your own

rights. In the U.S. (and some other countries), you don’t need to

do anything special to obtain copyrights for your own images; you

implicitly own the copyright as soon as you create the image.

However, explicitly registering your photos with the copyright office

provides more legal protection, since it provides proof of

ownership. Refer to the copyright office in your country for

specific information on copyright laws. Note that explicitly

registering images with the copyright office typically involves a fee,

and can take months to complete.

As we’ll see in Chapter 11, adding a copyright

notice to each of your images via Photoshop is simple, and needn’t

interfere with

the aesthetics of the image (if done properly).

References for this section

- Stanford

Computer Graphics Laboratory [http://graphics.stanford.edu/gamma.html]

- Gamma

FAQ, by Charles Poynton.

[http://www.poynton.com/notes/colour_and_gamma/GammaFAQ.html#gamma]

|

|

|